In my last blog post, I discussed how I think that the way most people talk about BI and analytics is incorrect, how data is fluid, and some of the biggest issues I see when helping clients. I’m going to continue that discussion in this blog post, but pivot the conversation from what is wrong to some things we can do to change it.

As I’ve said before, the mindset that we bring to the table when working with data is a big part in determining our success. Changing this thinking is hard, and if you’re expecting a click bait list of “5 Easy Ways to Get More From Analytics”, you’re in the wrong place. We can however, move further from a state of immature data to mature data by challenging the status quo. Below is the first of a series of blogs that will provide my thoughts on how we can change.

Is it a Project, or a Service?

Yes, yes. I know what you’re thinking — “Another ‘as a Service’ thing? Seriously?” I don’t blame you for that either, with all of the PaaS, SaaS, IaaS, DBaaS, etc. out there, it is a bit annoying. But… bear with me on this. I’m thinking about this from an economic point of view, and I cannot help but think of data like a utility.

Laying A Little Ground Work

Let me start with some basic Econ 101. For any who are unfamiliar with the basis of modern economic thinking let’s begin with supply and demand. In a marketplace, we have suppliers and consumers. Suppliers, well, supply stuff — whether that be mobile phones, ride sharing services, concert tickets or whiskeys. And you guessed it, the consumers consume those goods and services that are supplied by the suppliers. If the suppliers notice that their supplies are not selling, they will typically lower prices to engage more consumers. And if more and more consumers are buying at a lower price, the suppliers will raise the price again. The same can be said for consumers, as they have the ability to affect the amount of goods and services in the market by spending their finite time and money on those goods and services supplied. When the suppliers and consumers agree on prices and quantities in the market, this is called the equilibrium.

So what is the point of the econ lesson (other than an excuse for me to talk about econ)? Let’s stop and think about these concepts for a moment and how they can relate to data in organizations; we’ll begin with the demand curve.

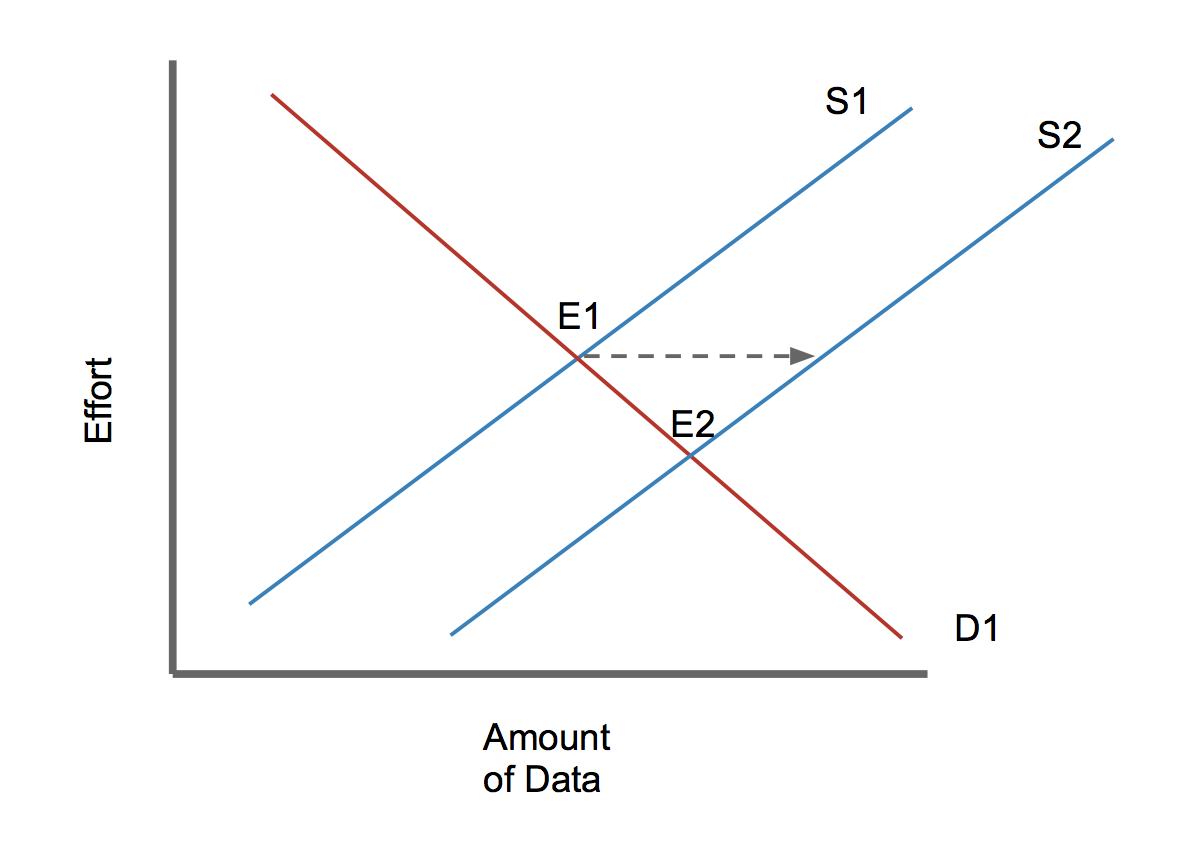

The business users have a demand for data; they need it to get their jobs done. If we look at a demand curve, we notice that only a few people want (or need) data that is high cost (left side). We can see that at low cost and high quantity, nearly everyone wants data (right side). Maybe a better way to think about price and quantity would be effort to insight and the amount of data, respectively. And this starts to make more sense, because everyone wants a ton of data that is low effort. Meanwhile, the appetite for taking data that is high effort to clean, prepare and analyze for a small outcome is low.

Now, let’s stop for a moment and think about the supply curve. Data suppliers aren’t willing to go through the effort of providing just a little bit of data; they prefer when there is sustainable demand. We can see that as the amount of data and effort go up, the higher the number of suppliers are willing to be in the marketplace. And this makes sense, because as more and more data is available, they higher the demand there will be for that data (we can save the law of diminishing returns for a different blog).

Point to Point Thinking

Of course, the service that being provided is data, infrastructure and tools to access it, and expertise to help make that happen. Some of you reading may be on the supply side of this, and some may be on the demand side. Now, we all know that projects happen in companies to bring more data into a new or current analytics platform. Or maybe the project itself is a new platform. However, if we think about data and it’s relevant components as goods and services, we stop thinking about it as a singular project. I think it’s best to think of these projects as an enhancement of a service, because in reality, that’s what it is. This new addition will lower the cost and increase the quantity of data for the consumers. How? Let’s take a look.

We can see our original supply curve, which is “S1” in the example to the left. We can also see that we have a nice steady equilibrium between the supply and demand curves at “E1”. However, by implementing a project that will deliver new content and data to the users, we have changed the amount of effort and data that our consumers use to get to those answers. You can see that “E2” — the new equilibrium — has lower effort and more data. A win-win for everyone in my book.

We can also think about how an initiative to engage more users will affect the demand curve. It would shift the curve to the right as well. And this point is salient because it begins to illustrate how fluid data is in an organization. Over time these projects will affect data demand and supply, the amount available and the effort involved to use that data. However, the marketplace will exist whether or not there are projects. There are still consumers to support, and there are still maintenance items to take care of. If we’re stuck in a mindset where we move from project to project, or initiative to initiative, we have lost the bigger picture by keeping our focus on the short term deadlines of a specific project. When this happens, not only does the vision for better data suffer, but concretely, our data services and thus, our consumers suffer as well.

Back to Fluidity

Because of the data marketplace that occurs in companies, it is better to think about data as a service or better yet, a utility that is provided by some in the organization. I say this because like a utility, modern businesses cannot work without data. (In economics, utilities also have a slightly different supply and demand structure, but maybe I’ll save that for a different blog post). This is also important because it helps frame the way that organizational data providers should be thinking about their role within the organization, how to interact with their consumers (the users) and how to structure their teams.

I also think that this is an apt analogy because as a consumer, I want as little interruption of service as possible. If my water utility has a burst pipe that prevents me from getting water out of the tap, I want them to fix it and let me know when service has resumed. If they are doing normal maintenance that does not effect me, I don’t want to hear about it. If the quality of my water is poor, I want to be able to call them and talk to a support agent that can address my concern, or at least take my complaint for further investigation. I want to be billed on time and without error. These are reasonable expectations, in my opinion. And the same can be said about data in an organization. Consumers want to be able to feel that they are heard and get the services they need. If service is interrupted, they want to know when it will be resolved. And, most maintenance items (patching, upgrading, code optimizing, etc) do not need consumer buy in (another issue I see from time to time), because these are items that should not have any direct effect on the consumer.

How does this translate to data suppliers and consumers? If we want uninterrupted service from data suppliers, they need to be given the resources to succeed. This may mean budget for new talent, it may mean more licenses for consumers to become power users, or it may mean effort to move to an agile framework. I also think it is in everyone’s best interest if persons developing new content (doing project work) are not pulled into “keeping the lights on” requests as well. Segmenting these functions into teams to heighten quality and on time delivery. Some organizations have these types of structures in place already, but many do not.

We also need to recognize that the consumers have an important role to play in shaping the data marketplace. If they are disengaged, how can the suppliers know what the preferences of the consumers are? If there is no dialogue, then suppliers are taking shots in the dark at what they think the consumers need and desire. And if consumers are leaving the marketplace because they do not find something they want or need, that is trouble for everyone. That situation breeds consumers who have to be their own suppliers as well. And we all know how that story ends…

This can be wholly avoided if we do two things. Consumers, speak up. Suppliers, listen up.